As Barack Obama’s second term as US president comes to an end, much has been said and written about his achievements, or in the case of the Guantánamo Bay prison camp, his failure to close it. One of his first actions upon being elected president for the first term in early 2009 was signing an executive order to the effect that Guantánamo would close within one year. Over 40 prisoners remain as he leaves office.

By mid-2010, the White House conceded that closing Guantánamo was no longer a priority. A senior official told the New York Times: “Guantánamo is a negative symbol, but it is much diminished because we are seen as trying to close it. Closing Guantánamo is good, but fighting to close Guantánamo is O.K. Admitting you failed would be the worst.” Sandwiched between his pro-Guantánamo predecessor and successor, this casts Obama’s administration in a positive light without having to do anything. The focus on what Barack Obama has not done at Guantánamo, however, should not deflect from what he has done. In some respects, Donald Trump will have to be rather creative if he wishes to outdo Obama’s legacy at Guantánamo.

The following are some of the highlights of Barack Obama’s presidency concerning Guantánamo that history may prefer to ignore:

1) The only war crimes tribunal anywhere since World War II where a defendant was tried as an adult for offences allegedly committed as a child took place under Obama. Canadian Omar Khadr was only 15 at the time of his alleged war crimes and arrest by the US military in Afghanistan in 2002. Obama placed a moratorium on military commissions when he became president, and Khadr was the first to be tried under the new Military Commissions Act 2009. Torture was admitted as evidence in the case which ended with Khadr pleading guilty in a secret plea bargain, which he saw as his only way of Guantánamo. He is currently serving his sentence under bail conditions in Canada, where he is training to become a first responder.

UNICEF condemned the trial, stating “The prosecution of Omar Khadr may set a dangerous international precedent for other children who are victims of recruitment in armed conflicts.” In international law, child soldiers are viewed as victims and not aggressors.

At the same time as Omar Khadr’s trial, an 88-year German former Nazi prison camp guard, who died before trial, was charged in a German youth court for alleged involvement in the deaths of hundreds of thousands of Jews at a concentration camp during World War II. A youth court was considered the appropriate forum as the charges related to offences that occurred when he was 21, and was thus legally considered a minor.

—-

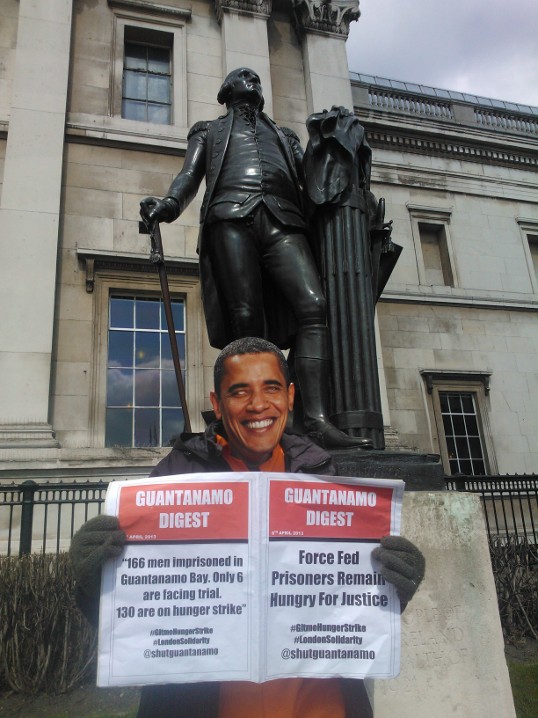

2) When Barack Obama became president, around 50 prisoners (20%) were on hunger strike. In 2013, a mass hunger strike broke out involving almost all the prisoners. It took the US government months to admit it and even longer to admit the violent methods used to quell the prisoners’ protest: rubber bullets were fired, dogs were set on the prisoners and hunger strikers were beaten and extracted from their cells to be force fed by nasal tube, which the UN called torture.

There was a complete breakdown in order at the prison at the time and prisoners were not the only ones physically and sexually abused. In 2014, two male soldiers were accused of the rape and sexual assault of female soldiers at the prison. One of them had the charges dropped against him in return for discharge from the army and the other was cleared of the rape charge and given two years for sexual misconduct and demotion with dishonourable discharge.

In 2015, another soldier was found guilty of hazing soldiers while stationed at Guantánamo in 2013. In one incident he ordered one marine to punch another so hard that he urinated blood. He was found guilty of the charges and demoted in rank.

—-

3) Four prisoners, all of whom were held without charge, died during Obama’s presidency. The first was Yemeni Mohammad Ahmad Abdallah Salih Al-Hanashi, who died in an apparent suicide. A recent e-book which looks at the medical and psychological factors of the death and that of another prisoner suggest this is not the case and that serious malpractice and the torture of prisoners had a role to play.

The death of the last prisoner at Guantánamo in September 2012 is also shrouded in secrecy and was dismissed as a suicide. Nonetheless, both the life and death of Yemeni Adnan Farhan Abdul Latif are testimony to the failure of Guantánamo. Following a car accident in the 1990s that left him with head injuries, he travelled to Pakistan for medical treatment he was too poor to afford in Yemen and was told a charity might help him there. Captured and transferred to the US military, he was quickly found to be innocent and was cleared for release as early as 2006. No independent autopsy was allowed and contradictions appeared in the official reports into his death.

Filmmaker Laura Poitras made this poignant film about the homecoming of his corpse:

—-

4) Throughout Obama’s presidency Yemenis made up the single largest nationality of prisoners and of those cleared for release. In 2010, Obama imposed a moratorium on returns to Yemen which was lifted for a period between 2013 and 2015. Although two prisoners were returned to Yemen from Bagram during this period, none were returned from Guantánamo.

During that period the Yemeni government announced plans to build a rehabilitation centre in the country for repatriated prisoners and The Economist claimed that the island of Socotra may be used for this purpose. The escalation of the civil war in the country put an end to such plans but demonstrate that Obama’s interest lay in closing the Guantánamo facility but not in ending the indefinite detention of prisoners elsewhere.

In addition, Obama extended indefinite detention without charge provisions to all US citizens under the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) 2012, which remains in force to date.

The continuation of the regime of indefinite and arbitrary detention without charge or trial is the quintessence of Obama’s legacy at Guantánamo.

—-

5) Not content with the abuse and torture of prisoners at Guantánamo Bay, Obama forcedly removed a number of prisoners to Algeria, where they were at risk of torture upon return. From 2009 to 2013 a number of Algerians were repatriated. Upon return they typically “disappeared” for a few days into police custody and some faced further arbitrary detention and torture, remaining under some form of surveillance and police supervision until now. This is in breach of the US’ international law obligations under the principle of non-refoulement, or not returning at-risk individuals to countries where they may face torture. One prisoner who was involuntarily repatriated is taking legal action against the US government.

—-

6) Before becoming president, Obama said that he would “reject the Military Commissions Act [2006]”. Instead, he simply revamped it into a 2009 model and never looked back. The Obama administration challenged the appeal brought by Yemeni prisoner Ali Hamza Al-Bahlul against his 2008 conviction three times; the first time Al-Bahlul was acquitted of all three charges against him; the current rehearing of the case is likely to make its way to the Supreme Court next. In the meantime, Al-Bahlul has been held in isolation at Guantánamo since 2008 as his case is volleyed around the US courts.

In spite of Obama’s faith in the torture-tinged military commission procedure, which falls below that of international standards for fair trials, a number of military lawyers have resigned in protest.

—-

7) Although no new prisoners arrived at Guantánamo under Barack Obama the practice of extraordinary rendition has not ended. This was starkly demonstrated in the 2013 Tripoli kidnapping of terrorism suspect Abu Anas Al-Libi by armed US military officials assisted by the FBI and the CIA. He was subsequently held incommunicado for several days on a warship before he reemerged in the US and was indicted in court. He died before trial in 2015. A number of other suspects who have been tried in US federal courts also “disappeared” and were held on US warships in unknown conditions before resurfacing following their “disappearance” usually in East Africa or Afghanistan. One such person is former British national Mahdi Hashi, who case is surrounded by much secrecy. In 2011, Somali Ahmed Abdulkader Warsame was the first such person to appear in a US civilian court following his kidnap and secret detention.